Associate Professor Jenna Burrell and Ph.D. student Elizabeth Resor Receive Google Faculty Award

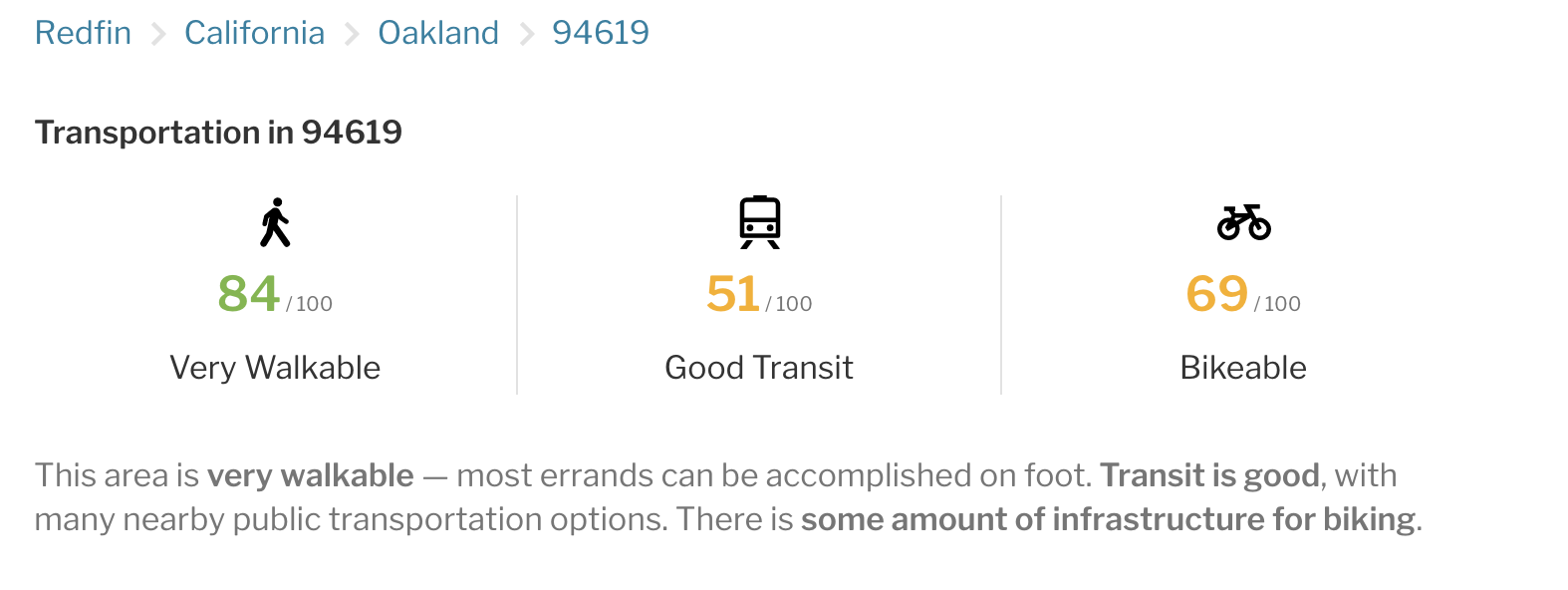

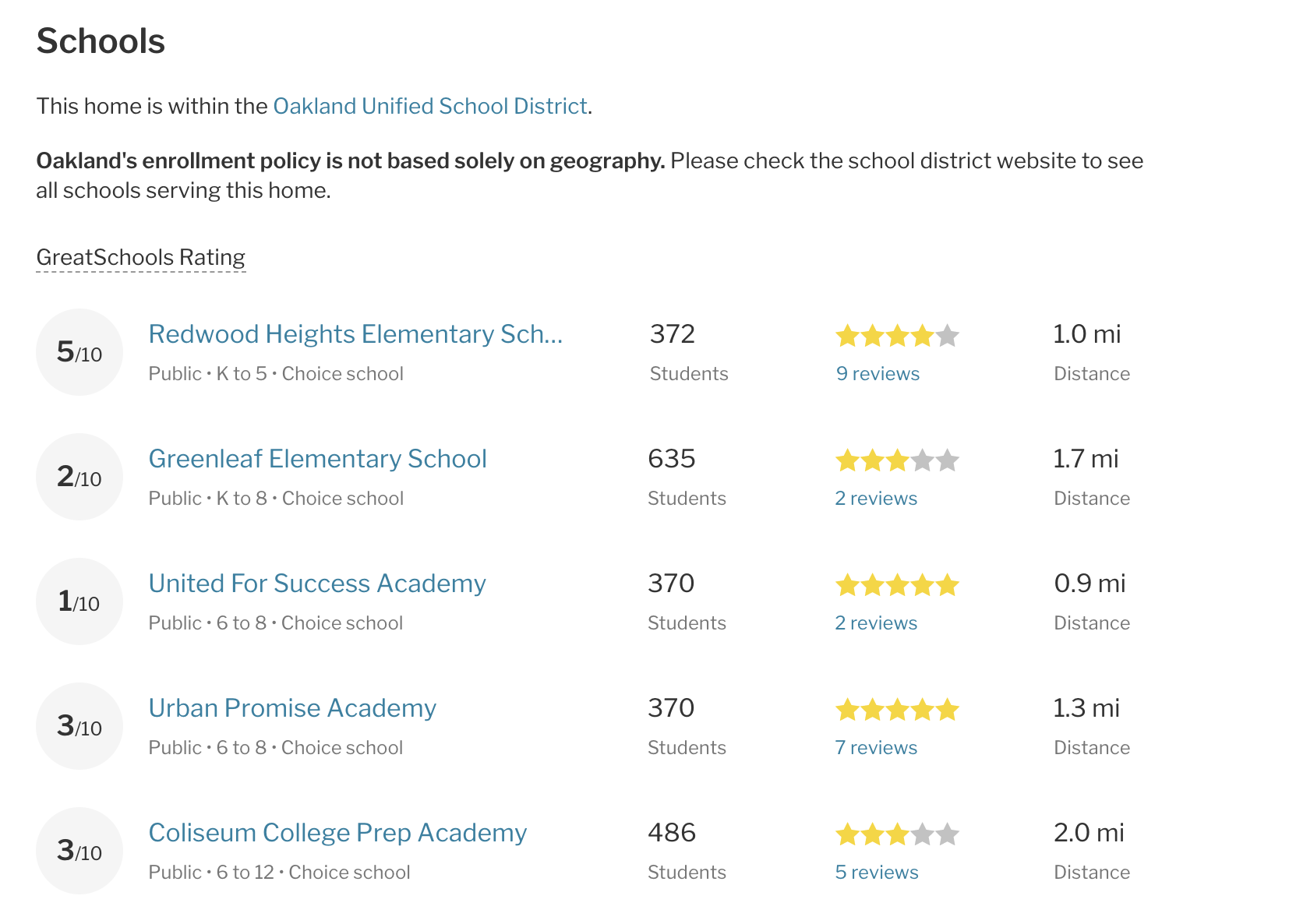

If you’ve ever perused homes for sale or read reviews of your local elementary school online, chances are you’ve come across a “Walk Score” of a neighborhood, or a “Great School” ranking. But how are these scores calculated? Do they affect the choices of people shopping for a new home, or trying to decide where their child should go to kindergarten? Do these scores play a role in entrenching patterns of bias that already exist in some of the data that is used to generate the scores?

Associate Professor Jenna Burrell and Ph.D. student Elizabeth Resor will examine these questions in their project “Scoring Space: Investigating models for interpreting neighborhood ‘scores,’” which was recently awarded a Google Faculty Research Award.

The award, which aims to “recognize and support world-class faculty pursuing cutting-edge research in areas of mutual interest,” will fund a year’s tuition and a stipend for third year I School Ph.D. student Elizabeth Resor, who will spearhead the project. With a B.A in architecture and a Master in City Planning, “Elizabeth's training is especially suited to look at these issues,” Burrell said.

Online real estate platforms like Zillow and Trulia include scores on crime, schools, and transportation in every property listing. The scores are provided by companies and organizations unaffiliated with the real estate website where they’re posted. When faced with these numerical scores, what do potential buyers make of them? “There’s a lot of research on how people writing the algorithms think,” Burrell said, “but how does the user understand the data being presented to them?”

Burrell and Resor also want to investigate whether and how these scores smuggle in bias inherent in the data sets used to calculate the scores, and to what extent users may be unknowingly perpetuating those biases by relying on what seem to be objective scores. For example, crime data can be tainted by racial bias, with neighborhoods of color often overrepresented because of a higher police presence. Standardized tests and student performance, two of the most prominent sources of school data, often have both racial and socioeconomic biases. When such data are crunched into these “opaque scores,” as Burrell calls them, and offered to real estate shoppers, it has the potential to “significantly alter patterns of human movement.”

Burrell and Resor will investigate these issues by interviewing people seeking to buy homes in Oakland. Focusing on Oakland because of its size and varied socio-economic groupings, they’ll use mock-up real estate listings and conduct interviews with approximately 40 potential home buyers (‘users’) to study how shoppers weigh the relevance of these scores and how they factor (if at all) into their decision making.

The researchers note that while there is a body of recent research on folk theories of algorithms in social media, their project will extend this work into a new area, that of school/crime/walking scores. Resor is especially “excited about the many paths we can take with this topic.” Given their prominence on real estate and apartment search sites, these scores have the potential to affect the actual fabric of how — and where — people live. Burrell asks, “What does it mean to have algorithms enter our daily living like this?”