If ChatGPT were a person, they’d be well-versed in the classic novels you probably read in high school. But there’s also a good chance they’d watch Doctor Who and know their way around a Dungeons and Dragons game.

In the recently published Speak, Memory: An Archaeology of Books Known to ChatGPT/GPT-4, I School Associate Professor David Bamman reveals much about what is known and remains to be known about the large language model (LLM) fueling ChatGPT.

The paper was co-authored by I School Ph.D. student Kent K. Chang, postdoc Sandeep Soni, and undergraduate research apprentice Mackenzie Cramer.

Because the datasets LLMs like ChatGPT and GPT-4 are trained on aren’t publicly made available, Bamman and his team had to first figure out what books were used in the data training set. Bamman, et al conducted a data archaeology by asking the platforms to complete a fill-in-the-blank exercise using different sources:

- 91 novels published before 1923

- 90 Pulitzer Prize nominees from 1924-2020

- 95 Bestsellers from the New York Times and Publisher’s Weekly from 1924-2020

- 101 novels written by Black authors, either from the Black Book Interactive Project or Black Caucus American Library Association award winners from 1928-2018

- 95 works of Global Anglophone fiction (outside the U.S. and U.K.) from 1935-2020

- 99 works of genre fiction: sci-fi/fantasy, horror, mystery/crime, romance, and action/spy

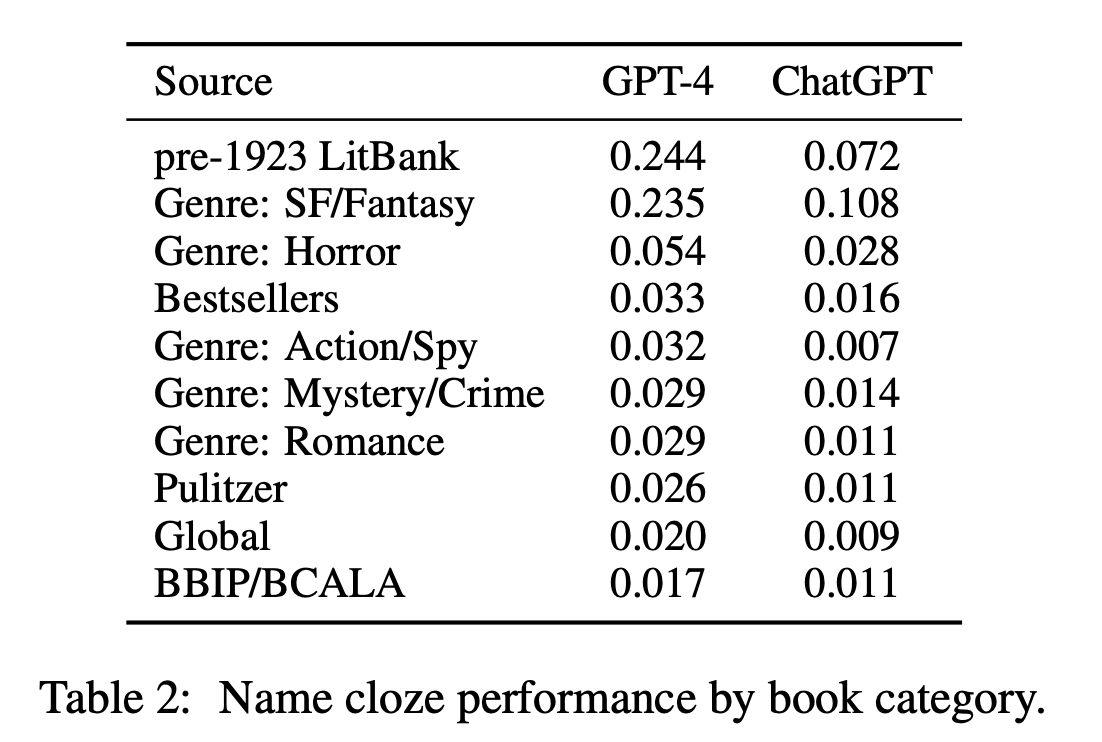

It worked like this: they’d enter a passage from a novel into the bot with a named character blocked out, then ask the bot to fill in the missing name. They did this 100 times for each piece of literature selected, and each book was then given a score based on how many times the bot was able to answer the question correctly. The higher the score, the more likely it was that the book was memorized (see Table 2)

Maybe it’s unsurprising that Bamman found the models were trained on materials widely available on the web.

This falls into two broad categories: books in the public domain (pre-1923 LitBank titles) like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or The Scarlet Letter, available online thanks to Project Gutenberg, which digitizes works of literature; and copyrighted material– sci-fi novels like Fahrenheit 451 or George R.R. Martin’s fantasy Game of Thrones– titles with particular nerd appeal that netizens have quoted at length over the lifetime of the web.

The bot doesn’t fare as well with Pulitzer winners, works of Global Anglophone texts, or works in the Black Book Interactive Project and Black Caucus American Library Association award winners.

Bamman’s experiment raises some important questions to consider going forward.

If the AIs have memorized certain texts and not others, do we, as users, understand what’s actually happening when we ask something of an AI? Because the datasets are closed, users have no idea whether the AI’s ‘brain’ is the Library of Congress or FanFiction.net. And what of representation? The lack of diversity (see Table 2) in the works uncovered by the Berkeley researchers is troubling: what might be the downstream effects of ChatGPT’s demonstrably limited background in terms of what it does and doesn’t ‘see’ when we ask it for things? There’s also the minefield of copyright issues to consider, including important questions about whether a model’s use of copyrighted materials falls under fair use.

For research that uses ChatGPT and GPT-4 for scholarly work, Bamman and his team posit that open models are needed to rectify the current challenges with the large language models driving the AI. “In order to really have an accurate sense of these model’s capabilities,” Bamman said, “knowing what’s in the training data is critical — we don’t want to be fooled by their seemingly amazing performance when they’re just memorizing the answers to the questions we’re asking them.”

And in the meantime, if you’re a college student looking to use OpenAI’s ChatGPT to assist you in writing an essay, here’s a tip: you might want to consider writing about The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy or The Hunger Games rather than Nabokov’s Pale Fire. The bot isn’t a huge reader of literary fiction. Yet.